As China closes both its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and the decade since the launch of its flagship Made in China 2025 industrial strategy, the moment invites a sober look at what has been achieved. Ten years after Beijing first announced its ambition to move from “factory of the world” to “world leader in advanced manufacturing,” both the plan and the strategy are reaching maturity together.

The 14th Five-Year Plan and Made in China 2025 were designed to improve the country’s economic KPIs into what policymakers now call “new quality productive forces,” a phrase that emphasises the pivot from quantity to quality, from input-driven expansion to technology-driven efficiency. Such change was focused on ten priority sectors where technological leadership would anchor future competitiveness, including robotics, aerospace, maritime engineering, advanced railway transportation equipment, new-generation IT, electric vehicles (EVs), advanced materials, biomedicine, energy equipment, and agricultural equipment’s.

The evidence suggests that the strategy is bearing fruit. According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) Critical Technology Tracker, China’s performance in strategic technological fields has shifted dramatically over time. While in 2007 China led in only 3 out of 64 critical technologies, the figure has jumped to 57 out of 64 in 2023, outpacing other advanced economies in the race to lead the frontier of research and development for strategic application in key fields.

Such impressive performance can be clearly observed in key segments, such as robotics, EVs, and green energy.

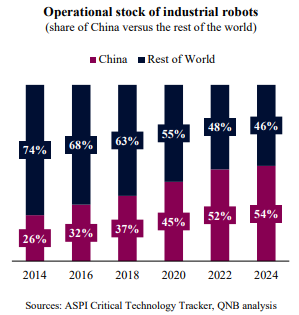

Robotics is perhaps the clearest illustration of Chinese technological leadership. According to the International Federation of Robotics, more than 295,000 industrial robots were installed in 2024, accounting for over half of global deployments. Those are strictly defined robots as “a programmed actuated mechanism with a degree of autonomy to perform locomotion, manipulation or positioning,” i.e., it needs to follow instructions from a control system, have physical hardware to move or apply forces, and perform physical tasks with defined levels of independence from continuous human control. The installed base now exceeds 2 million units, by far the largest worldwide. Even in terms of robot density, China leads with 470 robots per 10,000 manufacturing employees, having recently surpassed other industrial powerhouses such as Germany, Japan, and the US. This wave of automation marks the transformation of China’s industrial landscape from labour-intensive assembly to smart, data-driven production. This positions China as one of the leading countries in the world for automation after South Korea and Singapore.

The same leap is visible across other strategic sectors. China produced around 12.4 million electric vehicles in 2024, over 70 percent of global output, and Chinese battery manufacturers held a combined 56 percent of global capacity. In solar energy, the country commands more than 80 percent of global manufacturing capacity across the entire value chain, from polysilicon to finished modules.

The scale of China’s green transformation is even more striking when viewed through the energy lens. In 2024, clean-energy generation (hydro, nuclear, wind, and solar) rose by roughly 16 percent year-on-year. The International Energy Agency estimates that China accounted for almost half of all new renewable-power capacity added globally that year. In solar, China installed more photovoltaic capacity in 2024 than the rest of the world combined, and its wind-power installations are equivalent to the total cumulative capacity of the United States and the European Union. These figures underline that China’s decarbonisation is not a by-product of slower growth but a deliberate industrial project: producing more energy, of cleaner origin, with globally unmatched efficiency and scale.

What makes this transformation distinctive is the degree to which manufacturing, energy, and technology are converging. The push for advanced manufacturing feeds into the green transition through new materials, batteries, and grid technology, while the expansion of clean power lowers the cost base for further industrial upgrading. The synergies are now visible in export data, where the “new three” industries (EVs, lithium batteries, and solar modules) have collectively become one of China’s largest export categories, rivalling traditional electronics.

All in all, the shift from “quantity” to “quality” and from exporting simple consumption goods to exporting production systems signals that China was successful in re-positioning itself at the high end of global supply chains. Over the coming months, the discussions for a new 5-year plan and industrial policy cycle will gain momentum with a focus on key sectors emphasizing AI and semiconductors.

Download the PDF version of this weekly commentary in English or عربي